Appreciation: Fire on the Mountain, a Musical Intervention

Robert Hunter and Mickey Hart collaborated in a poignant plea for Jerry Garcia’s life.

The Grateful Dead was the most American of bands. With the divining genii of Jerry Garcia, Robert Hunter, Bobby Weir, Phil Lesh, Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, Bill Kreutzmann, Mickey Hart, Keith and Donna Godshaux, John Perry Barlow, and other members of the band’s extended family of contributors, the Dead drew from the deepest wells of America’s musical groundwaters — certainly from the great aquifers of rhythm & blues, country & western music, Southern soul, classic rock & roll, and country rock, but also directly from the tributary streams of sea shanties, old English ballads and folk songs, African American spirituals, ragtime, Delta blues, country blues, all other blues, jug band music, mountain bluegrass, regional folk strains, railroad and worker songs, roadhouse sounds and biker tunes, Cajun music, reggae, Dixieland, improvisational jazz, Motown, and (even) disco. The band added rye and sour starter and cooked this mash together into a hearty Northern California ferment.

The Dead’s musical mash included many covers of classic or traditional American tunes, like I Know You Rider, Not Fade Away, Morning Dew, Goin’ Down the Road Feelin’ Bad, Cold Rain and Snow, Good Lovin’, Big Boss Man, Johnny B. Goode, Big River, Mama Tried, Me and My Uncle, Big Railroad Blues, Hard To Handle (check out the excellent version on the 1971 live album Ladies and Gentlemen … The Grateful Dead), It Hurts Me Too, and Turn on Your Love Light.

But they also produced some of the most original of American songs, with melody lines most often by Garcia or Weir and perfect timeless lyrics, economical and jewel-like, usually penned by Hunter but sometimes by Barlow. Songs so wholistically American as Bertha, Cumberland Blues, Brown-Eyed Women, Jack Straw, Cassidy, Friend of the Devil, Ripple, Box of Rain, Loser, New Speedway Boogie, It Must Have Been the Roses, Operator, Candyman, Sugaree, Ramble on Rose, Brokedown Palace, Tennessee Jed, Franklin’s Tower, Wharf Rat, Till the Morning Comes, Touch of Grey, Truckin’, and Sugar Magnolia.

Two of their early studio albums, American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead, both released in 1970, are close to perfection. And has anyone ever written better song lyrics than the opening lines of Barlow’s Cassidy?

I can see where the wolf has slept by the silver stream

I can tell by the mark he left you were in his dream

This complex distillation of musical content and traditions, as rich as it is, does not by itself measure the full genius of the Dead. The total synergy of the band was only realized through live concert jamming, improvisational and always unique, with extended melodic riffs and intertwined instrumental segments and spacey transitions created organically, instinctively, on the spot through a group alchemy of the band, led by subtle onstage tells from Garcia, Lesh, and Weir. When touring, they played upwards of 80 concerts a year — over their 30-year history from 1965 to 1995, more than 2,300 concerts — nearly all recorded faithfully, though sometimes haphazardly, by the band (beginning with its first sound engineer, Owsley Stanley) and by its friends and followers, with recordings available through published albums, bootleg versions, organized compilations, and thousands of private unofficial recordings, many posted and now freely available on www.archive.org.

The alchemy of the Grateful Dead’s live stage performances depended on the spontaneous functioning of a mental network, an interconnection of the band members through coordinated patterns deeply imprinted in the neurons of their cerebral cortices and communicated through common muscle memories. Among the original core members of the group — Garcia, Weir, Lesh, Hunter, Kreutzmann, and McKernan — this single-brain network first formed organically through numerous all-night unstructured jam sessions they played in black-lit rooms and musty auditoriums at psychedelic “acid test” parties (including those organized by Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters) on the S.F. Peninsula and in Marin, Portland, and Los Angeles in 1965–1966.

Except for Pigpen, who mostly stuck to hard liquor, the active catalyst for the band’s essential live-jamming synergy was lysergic acid diethylamide. LSD became available in the Bay Area in late 1964 following the expiration of the Sandoz patent (Robert Hunter had actually first taken it along with Kesey in 1962 as part of a government-run experiment at Stanford’s VA hospital), and amateur chemist-suppliers — most particularly Owsley Stanley — soon began manufacturing and distributing acid hits for recreational use. (California didn’t criminalize the sale of LSD until October 1966, and Congress prohibited its possession under Federal law beginning in October 1968.) LSD-laced Kool-Aid launched the acid-test celebrants into a kaleidoscopic mind field of orphic jubilation, and for the musicians who played the background accompaniment to these black-light celebrations — particularly Jerry, Phil, Bobby, and Bill — it loosed them to wander through unfenced woods of shared sound hallucinations where they merged their urges and talents into new trails and patterns of musical exploration none of them had ever experienced on their own. This group jamming experience imbibed by the core members of the band in 1965–1966 became the essential psychic glue for the Grateful Dead’s concert performances going forward — from the beginning in the free-and-open street music days of Haight-Ashbury through to the very end of the line for Jerry and the band in 1995.

You can hear the improvisational style and free-flowing nature of these psychedelic musical wanderings in many live recordings of the Dead’s extended concert versions of songs and space-jam transitions from one song to another, like the Dark Star-St. Stephen combo from the album Live/Dead, recorded at the Fillmore West in San Francisco on February 27, 1969; The Other One from the Skull and Roses album, recorded at the Fillmore East in New York City on April 28, 1971; China Cat Sunflower into I Know You Rider from Europe ’72, recorded live at Olympia Hall, Paris, on May 3, 1972; and, also from Europe ’72, the Epilog and Prelude into Morning Dew, recorded at the Lyceum Theatre in London on May 26, 1972.

The Grateful Dead is forever associated with the legions of harlequin celebrants, the Deadheads, who followed the band from concert to concert in cult-like fashion, and for some portion of these devoted celebrants (though I believe only a minority fraction), LSD was also instrumental to their synesthetic reception and experience of the Dead’s live music. This fact became quite apparent to me in 1977 when I experienced my first Grateful Dead concerts while a student at Stanford. Though I never touched or took any LSD myself and never saw anyone take acid, I did have Deadhead friends at Stanford who said they took it — including one who flashed a little square of blotter paper that supposedly contained a hit of LSD. In late December 1977, several of these friends asked me to serve as a designated driver to a series of Dead concerts at Winterland Arena up the Peninsula in San Francisco.

The Grateful Dead played four nights at Winterland that month, culminating in a raucous New Year’s Eve concert featuring the loud revving of a big Hell’s Angels chopper onstage, and I attended three of these concerts, December 29, 30, and 31.

Winterland, the Dead’s favorite home venue and scene of The Band’s Last Waltz on Thanksgiving Day 1976, was a classic old ballroom and former ice rink located in the City’s Western Addition on Steiner Street between Post and Sutter (long since torn down and replaced by an apartment complex, 2000 Post). With an open concrete floor and a generous wrap-around balcony, Winterland had a capacity of 5,400. It was always “festival seating” for Dead concerts, and we staked out positions in a long line on the sidewalk outside the ballroom, where I well recall Bill Graham, the promoter of the concerts, passing out free buckets of Kentucky Fried Chicken to folks waiting in line. I remember we claimed seats in the front center of the balcony opposite the stage, and during the long sets, I had occasion to explore the whole arena, getting up close to the stage at times or taking in the tie-dyed spectacle of whirling Deadhead dancers on the fringes of the floor. What a slice of 70s culture (or counterculture)! You can get a feel for the experience by watching The Grateful Dead Movie, filmed at Winterland in 1974 and released in the summer of 1977 (getting stoked on the Dead, I caught the movie six times that summer while home in Portland after my freshman year at Stanford).

Here’s a photo of me taken in Portland in the summer of 78:

One of the friends I drove to the concerts in December 77 was evidently a particularly intensive user of acid, and he told me that his body built up some kind of resistance to LSD when taken on consecutive days, even though the chemical is such a potent hallucinogen. I believe he went to all four nights of those Dead concerts — Tuesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday — and he told me that by the fourth night, he had to take more than 20 hits of acid to produce the same hallucinogenic effect that he got from 2 hits on the first night. He acknowledged that all the LSD he had ingested would leave him with long-term lingering effects — and I vividly remember one day in the spring of 1978, when we were sitting eating sandwiches outdoors on campus, he suddenly lapsed into an acid “flashback” and abruptly excused himself and wandered off.

So, while drug use was of course endemic in the culture of many rock & roll bands coming out of the 60s and 70s, it was especially formative in producing what became the total musical phenomenon of and around the Grateful Dead. And unfortunately, LSD, as potent as it was, was not the only narcotic at play in shaping the history of the group. Jerry Garcia and other members of the Dead family smoked pot, popped a variety of amphetamines and other pills, and in the early 70s began using cocaine. Jerry was a heavy smoker, too, both of tobacco and weed, and in 1974 he started inhaling smokable heroin (called “Persian”). By 1975 (about the time he was immersed in editing The Grateful Dead Movie), Jerry had become addicted to heroin, on top of his serious dependency on cocaine.

Jerry’s own heroin addiction coincided with (and perhaps led to) an outbreak of heroin use among some of the roadies and other hangers on around the Grateful Dead enterprise, and there developed for the group and within the band’s extended family a wrenching and sometimes ripping schism between the old-time acid trippers and the new clutch of heroin users, as chronicled in the excellent 2017 documentary film Long Strange Trip, directed by Amir Bar-Lev.

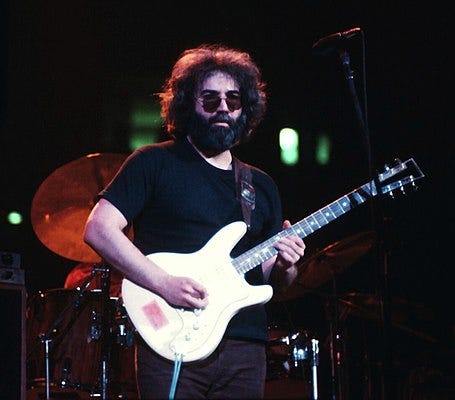

There could only ever be one Jerry Garcia. He was the lead-guitar impresario without equal, the master tune crafter, the father founder and face of the band — in sum, the prime mover, the spirit center, and creative genius who embodied the Grateful Dead. Hundreds of people (not just the immediate members of the band and their families) were dependent on Jerry and his musical fortunes as part of the sprawling enterprise that had grown up around him. Thanks in part to money-losing ventures, grasping business partners, and the band’s hyper-lax approach to intellectual property, live concert revenues were the principal source of support for the growing multitude of dependents. Money generated from relentless concert touring — both by the Grateful Dead itself and by Jerry’s other bands and concert acts — clothed and fed this extended tribe (and funded Jerry’s drug habits). Jerry felt acutely responsible for sustaining the life and energy of the tribe, and he drove himself to keep it all in motion.

By the middle of the 1970s, however, Jerry’s heroin addiction was threatening to destroy his life and collapse the entire world structure of the Grateful Dead. It was already obvious by the time I started going to Dead concerts in late 1977, and it became even more evident at concerts I attended in 1978 (when he was only in his mid-30s), that Jerry’s health was suffering, his vitality was in rapid decline, and it was affecting the group’s performances: he often slurred or forgot lyrics, his voice was sometimes very weak, his hair was turning gray and he was gaining weight, and his guitar playing was inconsistent in quality, at times only a dull echo of the spontaneous brilliance and ringing clarity heard in recordings from the band’s heydays from 1969 to 1972. For the last two decades of Jerry’s touring career, concertgoers (other than those too drugged out themselves to care much) entered the arena each night hoping against hope that Jerry would be looking and sounding a little better and that his playing would be strong and lucid, at least in portions.

I believe it was in response to this swelling health crisis for Jerry Garcia and the band that Mickey Hart and Robert Hunter came together to compose the finished version of the song Fire on the Mountain.

Mickey Hart, the Grateful Dead’s second drummer and percussion specialist, was (and remains) one of the most committed and accomplished scholars, teachers, and performers of the drumming arts of the world.

Mickey first laid down the mesmerizing pulsating soul-stirring drumbeat and percussive continuo for Fire on the Mountain in an earlier proto form, recorded (with Jerry on guitar) in the barn studio on Mickey’s ranch in Novato, California in 1972–1974, along with a chanted, rap-like precursor (most likely penned by Hunter) of the chorus and portions of the verses. Robert Hunter then reworked the lyrics, and he and Mickey put the finishing touches on the song, probably at Mickey’s ranch in late 1976 or early 77.

The Grateful Dead debuted Fire on the Mountain at Winterland Arena on March 18, 1977, and they performed it in concert 253 times between 77 and 1995, usually paired with Scarlet Begonias in the combo Deadheads call “Scarlet Fire.” The song was included on the Dead’s studio album Shakedown Street, released in November 1978. One live version often cited for its excellent guitar riffs, building to a great crescendo, is from the legendary Barton Hall concert at Cornell University, May 8, 1977; unfortunately, however (as happened all too frequently), Jerry garbled the lyrics and omitted one verse in the Barton Hall version. Among my favorite recordings is the more relaxed three-verse version performed at Winterland on October 22, 1978, included in the Complete Road Trips compilation.

Hunter has said that the song’s chorus (“Fire, fire on the mountain”) was originally inspired by an approaching wildfire that burned several properties near Mickey’s ranch while Hunter was staying there. The “fire on the mountain” word theme, of course, is found in several traditional American folk songs. And the fact that portions of the lyrics were penned in 72 or 73 certainly shows that the song first sprang from inspirations unrelated to Jerry’s heroin addiction. But whatever the initial motivations for the song, when Hunter was revising and polishing the lyrics and he and Hart were working to complete the song by early 1977, the crisis that was unfolding in the Grateful Dead’s world because of Jerry’s addiction must have imbued the song with deeper meaning, new urgency, and heavy poignancy.

For the Dead, Jerry Garcia certainly was “the Mountain” — the mountain top, the Moses of the Mountain for the tribe. (Perhaps coincidentally, back when the members of the band were living at what I think of as the “brokedown palace,” the old Victorian rowhouse at 710 Ashbury Street, Jerry’s girlfriend at the time, Merry Prankster Carolyn Adams, was known as “Mountain Girl.”) By 1977, Jerry’s heroin addiction surely struck Robert Hunter and others as the rolling flames of a fearful fire, threatening to rage over and consume the mountain for those who loved and depended on Jerry. Years later, indeed, Hunter was quoted as saying, “All I can say is it more or less ruined everything, having Jerry be a junkie.”

The song’s first verse speaks to the “Long distance runner” who’s “playing cold music on the bar room floor/ Drowned in your laughter and dead to the core,” and it warns, “There’s a dragon with matches loose on the town/ Take a whole pail of water just to cool him down.” Except for the significant change to “Long distance runner,” which replaced the original phrase “Wrong way Billy,” these particular words were first written years before; nevertheless, they, too, must have taken on a new sadder meaning for Hunter and Hart in 1977. In its finished form, I’m convinced the song is now addressed to Jerry: He’s the long-distance runner who’s trying to spread joy and laughter by staying in motion, playing his music day in and day out in an unrelenting concert schedule, while his addiction is killing him at his core. And heroin obviously had become the dragon threatening Jerry and the band: in street slang, smoking “Persian” — inhaling the fumes of heroin heated on tin foil — was known as “chasing the dragon.” These new meanings had to be top of mind for Hunter and Hart in 77.

Significantly, the second and third verses of the finished song are not found in the earlier versions; they appear to have been written by Hunter when Jerry was in the grip of his addiction, and their relevance to Jerry’s health crisis is clear to me. Here’s the second verse:

Almost aflame, still you don’t feel the heat

Takes all you got just to stay on the beat

You say it’s a living, we all gotta eat

But you’re here alone there’s no one to compete

If mercy’s in business, I wish it for you

More than just ashes when your dreams come true

Jerry was “aflame” with his addiction, even though he pretended not to feel it, and the rest of the band could see he was struggling with all he had every night to perform up to his standards and “stay on the beat.” Jerry insisted on continuing the grueling concert schedule because it provided “a living” for the Dead’s entire extended tribal enterprise, and they “all gotta eat.” But Hunter was urging Jerry to cool down and take care of his own health first, because he was in a league of his own — there was no one who could take his place if he flamed out, no one who could fill the role he filled for the world and for the Dead family. And, in something like a prayer, Hunter was wishing for mercy for Jerry and for the fulfillment of his dreams, free from the toxic ashes of burnt heroin.

The third verse brings the meaning home:

Long distance runner what you holdin’ out for?

Caught in slow motion in your dash to the door

The flame from your stage has now spread to the floor

You gave all you had, why you wanna give more?

The more that you give, the more it will take

To the thin line beyond which you really can’t fake

Jerry’s heroin addiction had spread out like a wildfire to other factions of the extended Dead tribe and was consuming many lives beyond his own. And Jerry could not keep the family enterprise sustained or get it back on track by giving more to his performances — the more he would throw himself into the grind, the more it would consume him, and at some point soon, he would inevitably cross the line into self-destruction, where he would lose all remaining ability to “fake” it, any last hope or delusion of keeping up the charade.

How poignant, and what a sorrow Hunter must have felt and expressed through these words! The friendship between Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter was the oldest and longest creative relationship at the heart of the Grateful Dead: They first became friends on the S.F. Peninsula in 1961, and they remained close friends and collaborators until Jerry’s death.

I wonder whether Jerry consciously understood and felt the personal plea that Hunter and Mickey Hart were making to him when he sang the words of Fire on the Mountain so many times onstage? I have to believe that at some level in his psyche, he did absorb the truth and urgency of the message the song carried for him. If Hunter and Hart had been open and heavy-handed about the song’s real meaning, Jerry probably would have outwardly recoiled from the song, and might even have refused to play it. But it was never Robert Hunter’s way to go into detail about the meaning of any of his song lyrics; he let the songs do their own speaking and deliver their own force. Maybe Hunter and Hart didn’t even privately discuss between themselves the full weight of feeling the song had taken on.

Sadly, in any event, Fire on the Mountain did not fulfill what I conceive to be its hoped-for prophecy — Jerry’s heroin addiction continued to burn and consume him after this attempt at a musical “intervention.” Eight years later, in January 1985, things had gotten so dire that Hunter and other members of the group mounted an honest-to-goodness in-person intervention, which Jerry initially resisted. Following a drug arrest, he agreed to seek treatment in 1985, but then relapsed, and after recovering from a near-death diabetic coma in July 1986, he struggled up and down, off and on, with addiction for the rest of his days, finally, when it was too late, checking himself into a treatment center, where he died following a heart attack in August 1995.

* * *

In our own way, each of us stands on the mountain top of our individual existence, and most of us have others in our lives who rely on us to bring a degree of sustenance and joy to their world. If you’re reading this post and you think you may have a drug problem, PLEASE, PLEASE seek the professional help that’s available to you and reach out to your truest friends and personal support network. And if you’re a close friend of someone suffering from addiction, be an active agent to help your friend find support, assistance, and treatment. You are unique, and uniquely important to the world, but you’re not alone. Don’t let the fire consume your mountain!